|

S |

M |

T |

W |

T |

F |

S |

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

|

21

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

27

|

|

28

|

29

|

30

|

31

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forums10

Topics39,709

Posts564,481

Members14,611

| |

Most Online9,918

Jul 28th, 2025

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

Ah, the "Rosetta Stone" at last! Thank you so kindly.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

Would this particular pattern be possibly also called "Best English 4-Iron Damascus"? The four-pointed "stars" outlined between two of the "full" scrolls here are fairly distinct. On some of the better guns I've looked at, these "stars" are quite distinct, even in exremely fine patterns. I was told by somebody (can't remember just where or by who at the moment)in my travels that this was a distinction to look for in better quality barrels. I've seen at least two guns where this feature was/is very prominent; one was an early John Dickson Round action and the other is a 1891 Boss-barreled John Hobson sidelock gun. When I stretch my memory, I can also recall a lovely, early Woodward hammer gun (that was reputedly re-browned by Dr. Gaddy). Absolutely gorgeous stuff!

Last edited by Lloyd3; 01/15/13 03:44 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Feb 2006

Posts: 3,857 Likes: 120

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Feb 2006

Posts: 3,857 Likes: 120 |

Brother Drew, thanks for the lesson. I think Lloyd3 might be referring to this type of "star" pattern. This is on a L.C. Smith grade 2E, and not normally found on lower graded guns without being ordered.

David

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

What David said, and different from Etoile' Star  Turkish Star  Etoile' Etoile' with tiny stars within the scroll  Washington

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/15/13 04:52 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

All are beautiful, but that Elsie comes the closest to what I was describing. Incredibly even patterns with very distinctive "stars" seem to distinguish the more expensively optioned guns I've seen (along with the great wood, stunning engraving, fine handling characteristics, etc., you know- "best"). From reading Greener's book, I understand that "overworking" as he referred to it can lead to less tensile and/or "burst" strength, but with few exceptions, the top of the lines guns I've seen and handled from the damascus era seem to have these features.

FWIW: I've owned and shot laminated steel guns (in 20-bore, 70mm nitro proof) that were supposedly as strong or stronger than Best English 3-bar (the 1894 Field Trial comparisons seemed to at least indicate that) but the tubes looked like plain skelp to me. Nowhere near as pretty.

Last edited by Lloyd3; 01/15/13 06:14 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

Lloyd - both English and Belgian (some of suspect quality) Twist barrels were routinely marked 'Laminated Steel'

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/15/13 06:57 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

Weren't the Belgians more prone to that? Greener's missives were pretty hard on them (but of course, W.W. was hard on anything that wasn't his or "properly English"). It was my understanding that true English Laminated steel was pretty good stuff, and that it appeared near the end of the damascus era. My little 1894 Bland Hammer 20 had London Proofs for something like 950 BAR. BTW-your above photo captures it perfectly!

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

1891! That's right...didn't the laminated steel even beat out some of the far-more expensive fluid steel stuff? Killer photos, BTW

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

Where do the "chain" damascus patterns fall? I'm assuming they are Belgian because I've only seen them on American and European shotguns. A friend accquired a Francotte Model 14 project gun from the early 1890s that had a stunning pattern on it. Later Model 14s (likely from the 1930s) I've seen with fluid steel seemed quite plain by comparison.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442 |

I've read a couple articles on how the sourced tubes arrived in the U.S. of A. An 1907 article on Ithaca gives that the "rough bored barrels" arrived 50 pair per box being no more than 0.03" from the finished state. Cockerill steel, laminated twist, damascus, Krupp & Whitworth were noted as being sourced. The Krupp tubes are noted as having a soldier with a gun, so I wonder if the author meant the Sauer Wildmann trademark? Also the Whitworth tubes had a serial number and a certificate. I assume this was standard and the other American makers received similar boxes.  Diagram of Belgian forging method and a "rough bored barrel" which was a tariff exception or taxed very cheaply. The article notes it took 5 or 6 days to bring out the contrast. Kind Regards, Raimey rse

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

Great photography Dr. Drew! Chain may be mid-grade, but the ones I've seen so-far are very attractive. Something else to consider; mid-grade guns from the 1880s seem to be far-better finished than mid-grade guns from the 1930s.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2001

Posts: 12,743

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2001

Posts: 12,743 |

Those chain bbls look like the ones on my FE Lefever, though chain is more common in the E grade Lefevers. Gun is SN 38,025.

Miller/TN

I Didn't Say Everything I Said, Yogi Berra

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

That is Mark's 10g Grade 2 Smith. The rough tubes may well have come from the same Belgian maker. Same infro here Raimey Nov. 30, 1895 Sporting Lifehttp://www.la84foundation.org/SportsLibrary/SportingLife/1895/VOL_26_NO_10/SL2610011.pdfHow Shot Guns Are Made and the Process Through Which They Pass Fully Explained The beginning of the manufacture of a gun is the barrels, and it is generally known that no barrels are made in this country except the rolled steel, which is used on the Winchester gun. All gun barrels are now imported, although an attempt was made a few years ago to produce them in this country, but with only partial success. England, Germany and Belgium supply most of the barrels, the latter country doubtless producing the larger quantity. All gun barrels, whether imported direct from the makers in Belgium, or through an importer in this country to the gun manufacturer, are received in rough tubes, which very much resemble a couple of gas pipes, but being somewhat larger at one end than at the other. These barrels or "tubes" as they are called, are merely tied together in pairs, with small wire and 40 to 50 pairs are packed in a box.

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/16/13 07:49 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442 |

Yes, Dr. Drew that is one of the other refs I've read by I couldn't put my cursor on it.

Kind Regards,

Raimey

rse

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Apr 2007

Posts: 135

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Apr 2007

Posts: 135 |

.....one of the best damn threads I have seen on the internet in a long long time. Thanks for the pics and explainations fellas.

Tom

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2012

Posts: 3,667 Likes: 1103 |

Dr. Drew: Your library is even more impressive these days, and it was darn good before (when I was haunting the LC Smith webpage a few years back). It looks like you've taken Dr. Gaddy's work and grown it substantially. Thank you so much for all you do.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

Since Drew introduced me to the doublegunshop forums, I have visited the site daily. Yea, I've been lurking. I am fascinated by the tremendous amount of information shared here. I've been checking this thread and thought I might offer my knowledge of damascus making, to help repay for what I have learned through this forum.

To understand how and why a pattern in damascus looks the way it does, you need to ask someone who actually makes damascus. This is what I do. A skilled damascus maker understands how to manipulate layers of material to create individual patterns. That knowledge can be used to reverse engineer how a pattern was made. The pattern tells a story, explaining how the material was manipulated to create it. I welcome your questions on how damascus patterns were made in gun barrels. I will do my best to explain them clearly.

Something in this thread interests me. It is the terminology used to describe the separate segments of the damascus pattern; "leaves", "scrolls", "1/2 scrolls". These terms are totally foreign to modern damascus makers. If I understand correctly, these terms were coined by Dr. Gaddy?

I'll be back to post up some information about damascus pattern development. If all of you are interested.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442 |

Culver:

I have a question for you: how many rifled pattern welded tubes have you held? And a follow up being how many tubes have you made that were destined to be rifled?

Kind Regards,

Raimey

rse

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

I've not held a rifled, pattern welded barrel.

The tube that I am at this time installing on a project, was intended to be rifled. I have not yet rifled it, as I am uncertain whether a future buyer of the piece will wish for it to be rifled. I can certainly pull the barrel off and rifle it at a later date.

Regards,

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

The image below offers a fair representation of the progression of pattern development that happens as a bar of twisted laminate is ground towards the center of the bar. Honestly, I have never seen anything like drawing K. The illustration in drawing J is more representative of what will be found at the exact center of the bar. As you can see, a significant amount of material must be removed before the "stars" begin to form. In my experience, approximately 1/3 of the material must be ground away before the pattern starts to display the typical crolle form.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

Thank you Steve! "It is the terminology used to describe the separate segments of the damascus pattern; "leaves" ( alternees), "scrolls", "1/2 scrolls". These terms are totally foreign to modern damascus makers. If I understand correctly, these terms were coined by Dr. Gaddy?" That is correct, but I'm not able to provide a specific reference. And for your interest; Indo-Persian "Twisted Stars" pattern  A Turkish percussion pistol barrel

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/17/13 09:28 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

You've no doubt seen this; the 'Lopin' (billet of iron and steel bars) prior to rolling Top: Etoile'/Star Left: Double 81 Bernard Middle: Extra-Fine Crolle Right: Washington  Etoile' I believe in Sachse

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/17/13 09:35 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Feb 2009

Posts: 7,714 Likes: 347

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Feb 2009

Posts: 7,714 Likes: 347 |

Thanks for the pictures folks.

Just guessing, but if there's a dark layer in the center of the stack, is 'K' possible. I'd also think 'J' would have at least a little tilt to the stars to at least follow the pitch of the twist. Maybe not though, interesting to reverse engineer, or try to, the great patterns that can show up.

I like to watch if a barrel maker was able to maintain their pattern through the entire barrel. The good makers must have known their stuff, not to change the pattern through uneven grinding as the barrel tapered breech to muzzle.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 4,598

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 4,598 |

The 1st step is controlling the rate of twist. To the best of my knowledge this was never written down, but passed from master to apprentice.  They were able to form any image they choose. This is just one cross section from a series that are on display in Liege,  Pete

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Nov 2012

Posts: 57

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Nov 2012

Posts: 57 |

I've seen damascus barrels with the name of the gunmaker incorporated in the pattern. How did they do that, given that you need to remove one third of the material before the pattern begins to show? Another lost art?

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

I will begin with an explanation of damascus steel and the methods used to create it. Once I have established the basic understanding of what damascus steel is and how it is made, I will circle back to answer your specific questions about it. Be patient; this could become a very long thread.

The making of pattern welded damascus, is the purposeful manipulation of layers of chemically different materials to create a pattern in the surface of a finished product. The patterns are made by manipulating edges of the layers to the surface of the finished piece where they will form a predefined pattern. As the elements are chemically different, they will be differentially affected by etchant and/or patina solutions to make the pattern visible.

The very simplest of damascus begins as a stack of flat materials. Typically, of alternating layers of two chemically different types of steel, or of steel and iron. The stack is forge welded into a solid mass, producing what today in the US, is commonly called a billet. Older terms were faggot and lopin, and I'm sure other names in different parts of the world. This billet is then drawn out by forging, pressing and/or rolling, into bar stock.

It is entirely possible, by very controlled dimensional reduction to maintain the layers in their original flat arraignment. The resulting pattern will be of simple straight lines. As there is little aesthetic appeal in a straight line pattern, the material is typically manipulated to displace the layers relative to their original positions in the billet. This is often done by mechanical manipulation, or a combination of stock removal plus mechanical manipulation. In the damascus pattern that we today call "random pattern", the mechanical manipulation is simply from the impact of the hammer on the layers of material. Each hammer blow displaces the layers and results in a circular pool shape in the surface of the finished piece. Overlapping hammer blows create overlapping pool shapes, the final appearance having what many call a wood-grain effect.

More purposeful manipulation of the layers can be accomplished by twisting, forging at an angle to the arrangement of the layers, stock removal by cutting through the layers and then forging the stock flat to raise the cut-through layers to the surface, or by pressing the layers with pattern dies to raise layers into the die pattern and then grinding of the raised areas to expose the upward turned edges of the layers. The billet can also be cut into angular sections, that are then restacked to organize the layers of material into a specific pattern. The restacked segments are then forge welded into a solid billet. The patterns possible are absolutely endless. Many modern damascus smiths who specialize in very complicated patterns, use "Play-Doh" to plan for the creation of damascus patterns. Using different colors of "Play-Doh" they can formulate a manipulation process to create specific patterns in steel.

Another form of damascus pattern creation is what we today call mosaic damascus. In mosaic damascus, elements are stacked in an arrangement to create words or pictures. The picture that Pete posted of the rampant lion, is an excellent example of early mosaic damascus (thanks Pete!!). The lion was created by stacking small square rods of material together, then surrounding them with rods of a different material. This stack then being forge welded into a solid mass. To make assembly and welding easier, these arrangements of materials to create pictures and words are typically much larger than will be desired in the finished product. Once welded together, the stock will be dimensionally reduced as evenly as possible, so as not to introduce distortion in the design. After a degree of size reduction, the design is often stacked into another assembly of elements, to again be forge welded into a solid mass for additional reduction to a dimension suitable for use in the finished product. In this way, a picture, such as the rampant lion may be assembled with an original dimension of perhaps 3 inches tall. It can then be dimensionally reduced to the size of a pin head for use in the finished product.

Early mosaic damascus was typically assembled from square rods , or other dimensional stock; as seen in the rampant lion photo. Modern mosaic damascus is often made by using water jet or EDM machines to cut out the shapes. Nickel is often used for the primary shape in modern mosaic damascus, as it resists the etchant solution and will display prominently when surrounded by high carbon steel. The primary design shape can be placed into a perfectly fitted hole, cut into a section of high carbon steel by the same water jet or EDM process. This assembly is then forge welded together. Or, the primary shape can be placed into a steel container, such as a piece of pipe, then powdered steel is poured around the primary to fill the container. The container is then sealed and forge welded into a solid mass.

To be continued…………

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Nov 2012

Posts: 57

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Nov 2012

Posts: 57 |

WOW.Where else can you get this great info? I want more damascus guns and knives just to be around this interesting technology.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442 |

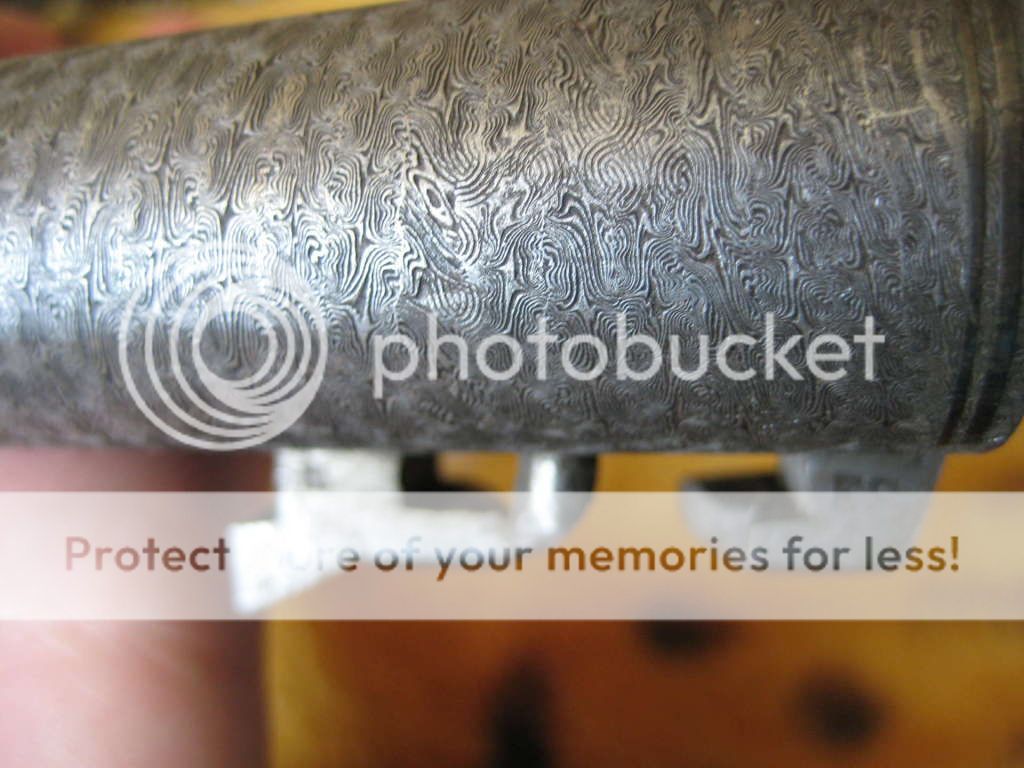

Drew, how do you fancy this example? It may be yours? I have it as a Ferlach sourced but I don't remember. Kind Regards, Raimey rse

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

It's an acid etched probably 4 Iron Hufnagel.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442 |

Thanks Drew. What's that disturbance in the force there?

Kind Regards,

Raimey

rse

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

Can't say Raimey. It's not uncommon at the breech, where the ribband is thickest, to lose some pattern symmetry.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

Raimey,

Not sure which “disturbance” you are asking about, as I see at least two.

The circular defect near the midddle of the photo appears to be from forge scale on the anvil being pounded into the damascus, causing a displacement of the edges of some of the layers.

There is an H shaped defect very near the breech end. This is easier to explain. This is caused by decarburization of the steel element in the damascus, due to it being exposed to the forge fire for an extended amount of time. Whenever steel is in the forge fire, carbon is being burnt out of it. The decarbed steel becomes simple iron and etches white. The H shape was caused by welds that were not quickly closed and were open in the fire for several more heats than adjacent areas.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

What a blessing to have a contributor who has actually done, rather than just read! "The decarbed steel becomes simple iron and etches white." I thought iron stained black?? More examples that are now explained

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/26/13 10:29 AM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/26/13 10:41 AM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Feb 2009

Posts: 7,714 Likes: 347

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Feb 2009

Posts: 7,714 Likes: 347 |

That was my pure guess about that oblong bullseye defect(?). Maybe a scarf joint, one strand curving a bit out of the barrel then when it was ground even it showed a little like and end not edge pattern. Thanks Doc Drew and Steve for the interesting contributions.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Aug 2007

Posts: 12,202 Likes: 442 |

Steve:

Yes, you correctly identified the culprit in the middle of the image. I surmised it to be heat related but never considered foreign material. Is there a time span during the day you prefer to roll your own?

Kind Regards,

Raimey

rse

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Dec 2001

Posts: 1,024 Likes: 84

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Dec 2001

Posts: 1,024 Likes: 84 |

I have been a member on this board for several years now and I have to say that I think this thread is the most interesting, informative group of posts I have seen in all those years!! It was this board and a couple of e-mails and telephone conversations with Dr. Gaddy that turned my thinking around about Damascus. I did own two Damascus pieces, a Remington and a LeFevre, but I let the LeFevre go in exchange for something else that had caught my eye. I shoot the Remington regularly. Thanks to all and to Dave for this wonderful source of information.

Perry M. Kissam

NRA Patriot Life Member

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/27/13 10:41 AM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jun 2002

Posts: 73

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Jun 2002

Posts: 73 |

This is truly a wonderful and informative thread. Thank you to all who contributed.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

Glad to help out.

Last edited by Steve Culver; 02/05/13 03:54 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490

Sidelock

|

OP

Sidelock

Joined: Jan 2006

Posts: 9,819 Likes: 490 |

Another revelation thanks to one of the primary contributors of images to DamascusKnowledge. Joe Wood's Lindner Daly with a change in the pattern from Corche at the breech  Transition from Corche at the breech tube segment (on the left) to Toncin at the muzzle segment  Toncin at the muzzle  A Remington 1894 EE "Ohonon 6 S.T." with the same pattern change Corche at the breech, along with some of the most tasteful engraving by any U.S. maker  Changing (somewhat asymmetrically) to Toncin  I believe the tubes started with the same pattern, but the thinner muzzle segment was ground more deeply changing the appearance

Last edited by Drew Hause; 01/28/13 01:41 PM.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Sep 2012

Posts: 129 |

The question has been raised about the coloration of the iron and steel elements in damascus. The smith will select materials for the elements in the damascus and then also the finishing chemicals that will create the desired appearance in the finished product. The color of the material after etching is determined by the alloys in it. Steel with a manganese content will typically etch black. Iron will etch gray through charcoal. Nickel will produce silver and chromium a light gray. The smith can use several different types of steel for his damascus and create layers in the pattern with varied shades from silver through black in the oxides formed by the etchant. But, there’s more. If the damascus is deeply etched, it creates topography (high and low areas) on the surface of the material. Whatever element that is least affected by the etchant will be proud of the element that was more eaten away by the etchant. When lightly sanded, this higher element will become lighter in color, or silver. Typically, it is the higher carbon content material (steel) that etches quicker. This would leave the iron layers standing above the steel layers. So after sanding, the iron would finish silver. If the damascus is then blackened or browned after etching and sanding, the colors could again change, depending on which element has the greatest affinity for the coloring chemicals. So, it would be a stretch to categorically state the either the iron or steel will always be a certain color. It is all dependant on the finishing process. In the photo posted earlier of the defects in the barrel pattern, it was obvious that the condition was caused by decarburization of material that had been exposed to the fire for an extended period of time. Decarburization would have occurred over the entire surface of the barrel tube during the forge welding and shaping process of the tube. The decarburized outer material would be ground away during the finishing process on the tube. In the area of the flaw however, the exposed edges of the material extended below what would become the outer surface of the finished tube. Once the welds were closed on the decarburized material, there was no possibility to grind them away in the finishing process. Surface decarburization is something that is critical for a bladesmith to understand. A blade must be forged with enough material left to remove from the outer surface to eliminate all decarburized steel. This is especially critical at the blade’s edge. The thin area of the edge is very susceptible to decarburization. Carbon loss from the steel at the edge will cause a loss in hardenability of the steel and result in inferior edge holding ability. It was long thought that it was possible to increase the carbon content in steel by using a reducing fire in the forge. A reducing fire being one that had insufficient blast to sustain complete combustion of the forge fuel and therefore leave available carbon in the forge atmosphere that the steel could absorb. Metallurgical testing in recent years has disproven this concept. Decarburization is especially problematic at the heats required for welding damascus. The high blast rates necessary to bring the fire and steel to a welding heat will certainly cause decarburization. Another fairly recent metallurgical learning that can affect the appearance of finished damascus is carbon migration. It was long believed that forge welding high carbon and low carbon steels together would result in layers with the same carbon content as the original steels. It has been metalurgically observed that carbon will migrate across the weld boundaries from the high carbon steel into the low carbon steel. The carbon is essentially trying to form an equilibrium throughout the matrix of steel. This migration happens in a relatively short amount of time and happens quicker at higher temperatures. So if two steels are used that only have different carbon contents and no other alloying difference between them, there is a possibility that carbon migration will render them substantially the same by the end of the forging process. Being nearly the same, they would not be so differentially affected by etchant and coloring chemicals. This could be a plausible explanation for damacus barrels that do not display a distinct pattern. Carbon migration can be stopped by placing nickel between the layers of steel. This is often done by modern damascus smiths. The result is a very high contrast damascus. The nickel finishes bright silver and will not color if the damascus is blackened. Nickel is not a suitable material for use in a knife blade, as it will not harden, so this combination of materials is only useful for knife fittings or other damacus items that do not require heat treatment for hardness. A question I have concerning old damascus gun barrels is whether the silica content of the wrought iron used for barrel making had the ability to mitigate carbon migration. There is not much wrought iron used in modern damascus, so I know of no testing that has been done in this field. I have sent a piece of an old damascus barrel to a friend and fellow knifemaker, Kevin Cashen. Kevin is arguably one of the most knowledgeable metallurgists on the planet. I have asked Kevin to do some testing on the barrel section, to include carbon migration examination. Kevin’s web site includes a tremendous amount of metallurgical information and is worth a visit. Cashen Blades Speaking of heat treatments; I find no mention of heat treatment processes performed on the barrel tubes in any writings contemporary to the manufacture of damascus barrels. I suspect that many of these barrels contained a sufficient amount of carbon to have been capable of hardening, if heated to a high temperature and quenched. They likely would have then needed to be tempered, or annealed, to mitigate brittleness. As a brittle gun barrel is highly undesirable, I’m certain that the smiths avoided any rapid cooling of the tube from high temperatures. They were however, doing a type of heat treatment process that I am certain that they did not fully understand. I have read in several writings of the cold hammering of barrel tubes after welding. The tubes were not actually “cold”, but in blacksmith terms, at a heat that was too cold to effectively move the steel under the hammer. This would be a low red heat, down to a temperature of about 900 to 1,000 degrees F. Greener states that this hammering “greatly increases the density of the metal”. The interesting part is that the actual hammering was totally unnecessary. In the bladesmithing world, cold hammering of a blade edge has been taught for decades; the description of the process was called “edge packing”. The concept was that the hammering of the cold steel compressed and refined the grain structure of the steel, creating a smaller and tighter structure. The tighter grain structure would take a keen edge better and retain sharpness longer. Edge packing was taught to knifemakers as an essential part of blade forging until about 20 years ago. Finally, metallurgical testing was done, revealing that the actual hammering of the cold steel had no effect. In fact, it was probably detrimental, risking stress fractures. Too, logic will prevail, in that steel is a solid and solids cannot be compressed. So, no density changes can be made to the material by hammering. Still, changes that were visible to the naked eye occurred to the steel during this process. The surface of the steel looked smoother and actually looked denser. If a blade was heat treated and then broke in two, the grain in the cold hammered blade appeared much tighter and smaller. This was also very apparent in damascus blades. The finish of a damascus blade that was not cold hammered was coarse and grainy looking. So, I am certain that the barrel smiths also realized that their barrels had a better appearance after the cold hammering process. They too would have assumed that the hammering of the steel was making it denser; as that was the look that it had after the process. The phenomenon of grain structure changes is purely the result of the temperatures that the steel is heated to. At high temperature (such as forge welding heat) the crystalline structure of steel becomes very large. As the steel cools, the structure reforms into smaller crystals. However, one cooling cycle is not typically enough to reform all of the crystals. So, the steel is reheated again to a temperature that is low enough not to create large crystals and it is allowed to cool to a black heat again. The lower temperature is sufficient to promote the reformation into smaller crystals, without creating large crystals again. This heating to low red heat and cooling in room air to a black heat is repeated three or more times. The process is called thermal cycling, or normalizing. I am convinced that this is exactly what the barrel smiths were doing during the cold hammering of their barrel tubes. Addressing the questions about why stars in the damascus patterns will transition between white and black, requires an understanding of what the smith is doing and also working with. This is a bit of a generalization, but the layers of iron/steel in a damascus barrel will be around .003 to .010 inches thick. Every hammer blow displaces the material, both downward from what will become the surface of the finished piece, as well as in relation to the material immediately adjacent to the impact of the hammer face. The smith will utilize overlapping hammer blows to attempt to keep the displacement of the layers as even as possible. It is important to understand that the smith has no visual reference for what is happening to the pattern, other than the appearance of the work-piece surface and his experienced knowledge of what is happening to the layers inside the material. The pattern cannot be seen at all during forging, as the surface is totally covered in forge scale. Given the hundreds of hammer blows that fall on the material during the welding of the rods into riband and the subsequent welding of the barrel tube, it can be seen that the small margin of a few thousands of an inch in layer thickness make it impossible for the smith to place all of the layers in an exact position. If when the barrel is sent to the boring room, it does not completely clean out, it is returned to the smith to be forged down in that area to reduce the bore for additional reaming. The affect of this additional forging could easily show up in the pattern. A barrel that displays a short area where the pattern makes a sudden change could have been one that was sent back to the smith. The barrel grinder has no contribution to the pattern development at all. During grinding, the pattern cannot be seen. The surface of the barrel is totally in the white. If the bore of the barrel is not concentric with the outside of the tube, the grinder has no choice but to remove the excess material from the thicker side of the tube. Uneven grinding for whatever reason will affect the pattern. Control of a damascus pattern is something that every damascus smith deals with. You know what you planned for it to be. You forge it as evenly as possible. If you forged well, you will grind an even amount of material away and hopefully preserve the pattern. But, you never know for certain until the etch. Etching is like opening a present for the damascus smith. You hope to get something beautiful and if you have done well you will. If not, you discover you got the ugly necktie.

|

|

|

|

|

Joined: Feb 2006

Posts: 3,857 Likes: 120

Sidelock

|

Sidelock

Joined: Feb 2006

Posts: 3,857 Likes: 120 |

Steve, thanks. Your site is awesome.

A while back I had watched a Japanese Master Swordsman and the skills it takes to make one and the amount of time. It showed how a block of steel was heated then flattened, and another type of steel added to it and folded. Not unlike what you do with your knives.

David

|

|

|

|

|